The history of the construction of the Pele House, its surroundings in the Beek Mountains, Ottó Herman’s and Kamilla Borosnyay’s connection to Lillafüred – all these combine to create a historical unity of the objects and themes displayed in the room.

Dear Visitor,

During the editing of our publication, we had to consider the fact that the information of the exhibition is largely displayed on monitors in our spaces through digital technology: the personal homeliness of the Pele House, the intimate atmosphere of hospitality is thus not broken by the inscriptions, didactic explanations with inventory numbers and other, on the other hand, fundamentally important with data.

For this reason, our exhibition guide is a detailed presentation of objects, photographs and documents directly related to the life of Ottó Herman and his wife Kamilla Borosnyay.

Well, first of all, we are happy to welcome you to Pele House!

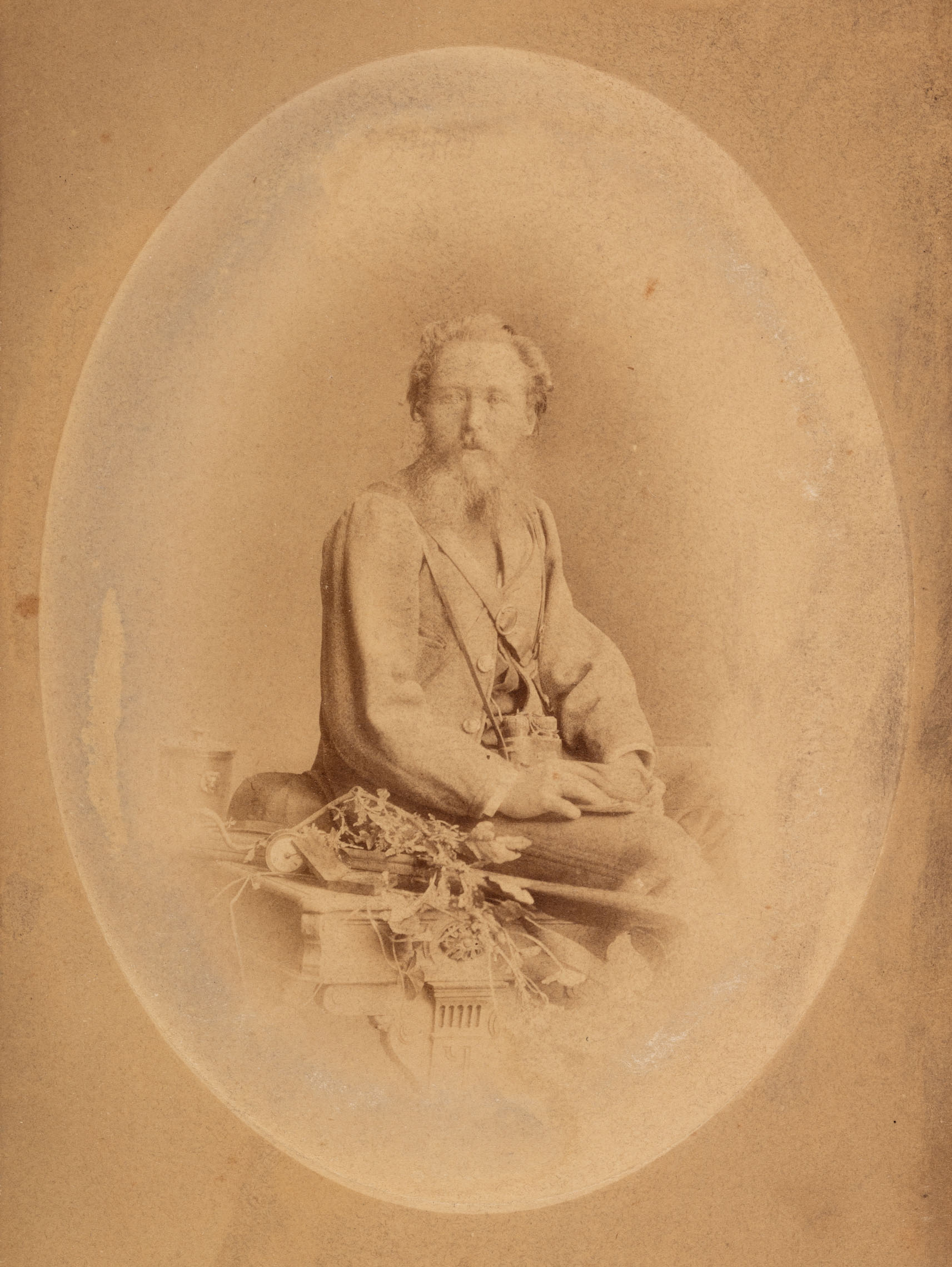

A picture of Ottó Herman as a young man

HOM HTD 53.247.48.

“It is certain that from an early age he had an irrepressible temperament, a wild, fierce nature, who avoided company, sought the wilderness, picked up crickets and insects, climbed trees… He would never stay at home and would run away whenever he could. In the summer, he roamed the woods, the meadows, the mountains, in the winter, he went ice-sliding and skating. His mother, in fear of him catching a cold, once hid her boots to keep him at home – so little Ottó ran barefoot out on the ice.”

(Kálmán Lambrecht)

The case of Ottó Herman’s telescope

HOM TGY 53.247.16.2.

“The best memories of my childhood smile back at me from the beech forest. How many times I have sneaked out of the house and into the beech wood, the only church where I can truly worship according to my heart and mind…. The crowns also touch like the arch of a Gothic bower, but the bower of the beech wood is a laughing green, and the sunlight sneaks through the holes, not the dirt of the attic, but the clear blue sky…”

(Ottó Herman)

Hunting photo from Norway

HOM HTD 70.48.2.

“He likes to dress up in odd outfits for this kind of outing. There are all kinds of them. He wears an English cork hat on his head, boots to the waist on his feet, a sheepskin waistcoat, a cob hanging over his shoulders, a haversack with scones and roasts on a black cord with a far-reaching view, a bull-skin canteen, a smaller canteen for cognac, a tin box on a chain, notes, and from the pocket (to make enough for the national genius) dangles the frills of a tobacco pouch made of ram’s horn. Now imagine Ottó Herman in this outfit.”

(Kálmán Mikszáth)

Ottó Herman’s birdwatching tourist chair

HOM TGY 2011.1.1.

“Imagine, please, the inhabitant of some distant point on the Hungarian plain, who has never seen a great city, who knows the thundering sky, the pouring rain, the bells of his village, the bells of the flock, the sounds that ring out in the solitude of the plain, nothing else. Let us blindfold the man, and then lead him up to Mount Gellert. He will hear the confluent roar of the great city, the whistle of ships and locomotives, the rattle and whistle, all these will be separated from the noise like the sound of crickets from the rustle of the meadow; but they will be strangers to him, they will not give him the concept of the great city, they will appeal only to his senses, his mind will at most wonder. He must open his eyes, he must get down from the mountain, and enter into the life of the city, and take stock of it from moment to moment, and then he will go up again, and then this murmur will speak to his senses: the shrill whistle will tell him that a ship is coming, the rattling will tell him what the factories are doing, and his ears will guide him through the moments of society, and the order in which society lives and moves will be before his mind. And so, it is with the musical world of the meadow. He who, blindfolded, listens to the sound of the meadow on the ignorant cockpit, will at most be uncomfortable with the cricket’s cry, with its chirping, crooning and dongling; but if he gets down from there, he will observe this little world in part and in part; from there he will reach the heights of reason, where he will learn that the smallest creature is, in its place, a full factor in the eternal order which we call nature.”

(Ottó Herman)

The flood of the Szinva stream in 1878 – which became known as the “Great Miskolc Flood” – swept away the family home. Ottó Herman’s childhood and youth were destroyed, but his strong attachment to his homeland remained. In 1889, Ottó Herman bought a plot of land in the Hámor valley, which two years later Count András Bethlen initiated the development of the valley into a holiday resort. Taking advantage of the favourable opportunities to buy land and build villas, he later bought further plots in the valley, which has an unrivalled location. Construction of the house, which still stands today, began at the turn of the century and was completed in 1903. Ottó Herman spent most of the summers of the last decade of his life in this house and wrote some of his scientific works here. The lush vegetation of the garden, the winding branch of the Szinva with its small mills, the garden pond and the two bridges have captured the imagination of both contemporaries and posterity. He sold the building to his nephew, Béla Szeöts, in May 1914. The family owned it until the Second World War. After that, the building deteriorated, collapsed and squatters moved in.

The Pele House has been owned by the Miskolc Museum since 1951. In the 1950s, a broad social campaign was launched to save it. After lengthy planning and preparation, the first renovation and reconstruction took place in 1963, and the first exhibition opened in 1964 in the former villa, which was converted into the Ottó Herman Memorial House.

A photo of the Pele house from the period

HOM HTD 80.153.13.5.

“The house was designed by my wife and the technical transmission was arranged by the forester Kárász. I know for a fact that the wall between the dining room and the kitchen was not built on the ground, but on an iron stake, and that the woodshed and the bathroom rather it is just leaning against the wall of the big house.”

(Ottó Herman)

A photo of the Pele house from the period

HOM HTD 80.153.13.3.

“A simple little villa, with a wide porch, richly planted with greenery, and comfortable… The plot is not large, but as Ottó Herman said, there is no prince in Hungary who has a park like his, for no one has such a rock in his garden; for one of the great rocks of the White Stone Moor, which borders the valley, rises just at the end of his house. In the garden, a small branch of the Szinva River winds through the garden, forming an island with two small, gurgling trees. Trout fizzing in the water, then a stork, natural arbours, tiny bridges – all the simplest, most beautiful.”

(Andor Leszih)

Memories of our host’s scientific and political career Fish and spiders, birds and beards…

Unconditional respect to Lajos Kossuth!

Ottó Herman’s scientific work was fundamentally determined by his close ties to the Bükk and the Hámor Valley. The roots of all the sciences he studied are to be found there: the flora and fauna of the mountains, the trout of the Szinva stream and Lake Hámori, the caves of the Bükk. It was this landscape that launched him into new challenges in new fields and united the polyhistor’s thousands of activities.

He has an unparalleled contribution to the creation of the Hungarian scientific language – even though he himself was a native German speaker and did not speak Hungarian until the age of seven. Many of his books also served a popular and educational purpose.

Ottó Herman’s name plate

HOM HTD 70.52.1.

“In addition to making the language as accessible as possible, I had to to be clean and to avoid dryness, so I’m trying to establish some kind of educational genre.”

(Ottó Herman)

Ottó Herman’s desk and armchair

HOM TGY 53.247.20-21.

“Of his bibliography of some 1140 items, 16 books and articles deal with the world of spiders, 42 with the vast host of insects, 184 with the army of birds, 26 with other animals, 8 with plants, 18 with economic and industrial questions, 47 with travel drawings, 29 with pictures of nature, 34 with the noble ideal of animal protection, 102 articles, books and studies on the broad field of ethnography: 78 articles and letters on miscellaneous subjects, 30 humorous writings, 387 political articles and speeches to the House of Representatives, 60 writings on cultural policy and 78 biographies and portraits of his contemporaries complete this rare and rich list.”

(Kálmán Lambrecht)

One of the greatest achievements of his scientific work is the three-volume work in which he described the spider fauna of our country. His work is still fundamental in this field of science. Ottó Herman began to study the life of spiders during his years in Cluj-Napoca. It was here that he wrote his study on the spider fauna of the Fields. After moving to Pest, in 1875 he took a job in the zoological department of the National Museum, and at the same time the Natural History Society commissioned him to work on the scientific study of spider species in Hungary. Between 1876 and 1879, his monograph on spiders was published in three volumes, including 34 new species among the 314 described. This work was unique in the literature of the time, aroused considerable international interest and is still a useful reference work for anyone interested in spiders.

Ottó Herman’s wallet

HOM HTD 70.50.2.

“I once mentioned to the general (Prime Minister Kálmán Tisza) in the corridor that a very eminent scientist of ours had been left out of the house and had thus found himself in very bad financial circumstances.

– You’re telling me to help him? – he snapped at me irritably. – How could I? Of course! Let him starve to death!

And with that he left me in the lurch, very angry, but at the end of the meeting he came up to me, tapped me on the shoulder and said gently:

– I asked Trefort to commission him or get him to write some work and give him as much money as he needed. But keep it a secret that my hand is in it, for as ignorant as he is, he will not yet find it to accept it.”

(Kálmán Mikszáth)

Ottó Herman is best known today as a natural scientist. His love of birds was instilled in him in the family home by his father. Later on, of course, fish, spiders, pelts and almost all forms of life inspired him to delve deeper, but he also paid constant and close attention to the world of birds. As a renowned scientist, he gathered around him young local ornithologists and developed a methodology of observation.

In 1888, he made a study trip to northern Norway for ornithological observations. The trip resulted in another magnificent book, a colourful and engaging travel diary of nearly 600 pages, entitled The Landscape of the Northern Bird Mountains. After the trip to Norway, he set about organising the II International Ornithological Congress. The meeting, held in Budapest in 1891, was one of the most successful of its kind in comparison with subsequent similar events.

The first result of this work was the establishment of the Hungarian Ornithological Centre in 1893, which evolved into the Institute of Ornithology. Also in 1893, the first bilingual journal on scientific ornithology, Aquila (the Latin word means eagle in Hungarian), was published. Ottó Herman personally also had a major role to play in starting the bird protection movement with government support. It was on this subject that he wrote his book On the Benefits and Harms of Birds, which became the has been an unprecedented success.

After retiring from politics and spending more time in Lillafüred, he published several papers on ornithology. The last two decades of his life were devoted to ornithology, but he did not produce a monograph of Hungary’s bird life.

Signed sheet of a Bársony-house hand axe signed by Ottó Herman

HOM HTD 58.434.1.

“On the 26th day of December last 1892, János Bársony, lawyer, the public prosecutor of the city of Miskolc, paid me a visit. As a token of his friendship, he presented me with a stone-age tool, which, together with two other pieces, had been dug out of the clay soil from a depth of about three metres by workmen during the foundation of his house, and which, because of their shape, looked like a bright stone… It took only a glance to recognise in the very characteristic piece in my hand a prehistoric antiquity of a prehistoric age, so to speak, of the prehistoric period of Hungary, which is in no way inferior to the famous stone sculptures of the Somme Valley, which all the authorities of prehistory consider to be of the Palaeolithic age, and typical of that period.”

(Ottó Herman)

Ottó Herman also wrote chapters of epoch-making importance in the history of Hungarian archaeology. Despite his late involvement in archaeological research, close to his 60th birthday, his achievements are extraordinary. Perhaps the most influential of these is his recognition of the so-called Bársony-house stone tools, made by human hands, and his proof that humans lived in the Carpathian Basin as early as the Ice Age. He published his discovery, setting a new direction for archaeological research in Hungary.

Twenty years of his life have been devoted to bringing Hungarian palaeolithic research out of the deadlock. From 1906, under the direction of Ottókár Kadič, large-scale cave exploration in the Beek began, not least thanks to the personal intervention of Ottó Herman with Ignác Darányi, then Minister of Agriculture. His greatest merit, beyond his own scientific achievements, is that through the cave excavations in the Beek he launched palaeolithic research in Hungary. For this reason, Hungarian archaeology honours him as the initiator and founder of prehistoric research.

Ottó Herman’s pen holder made of bear bone from a cave

HOM TGY 53.247.54.

“even on the tiny desk, Ottó Herman’s homemade penholder is made from the bones of a primeval bear from the Seleta cave”

(Budapesti Hírlap, 23 August 1928)

In addition to natural sciences, Ottó Herman was also engaged in ethnographic research, mainly on the characteristics of Hungarian fishing, pastoralism and folk architecture. Natural science, especially zoology, led him first to the study of Hungarian fishing and later to the study of Hungarian pastoralism and folk architecture. Fishing and pastoralism were the two main thrusts of his ethnographic research. He saw them as a unity and introduced the term “ancient occupations” into scientific language as a common name for them.

Ottó Herman’s regular fishing research began in 1883, when he was commissioned by the Natural History Society to write a monograph on fishing. In 1885 he published the large number of tools he had collected, and in 1887 he published the results of his research in two volumes (The Hungarian Fishing Book) with numerous illustrations drawn by himself. The fishing tools in the Ethnographic Museum are of inestimable scientific value. His collections of objects related to the study of fishing and pastoralism he founded the Hungarian collection of the Museum of Ethnography.

At the end of the 19th century, the emerging field of ethnography was inextricably linked to the great national and world exhibitions. Ottó Herman traced his own fishing research back to the 1885 national exhibition in Budapest, where he presented an impressive collection of the tools he had collected. He also wrote a trilingual guidebook for the exhibition, entitled Ancient Elements in Hungarian Folk Fishing, which was not unheard of abroad.

Ottó Herman’s most important exhibition in 1896, for the millenary celebrations as a collaborator in the millennial national exhibition. At his suggestion, the organising committee added herding to the themes of fishing.

Model of a hemp crusher mill from the collection of Ottó Herman

HOM TGY 53.247.59.

“Through his garden ran the shallow stream of the Sinava, and on it swirls the little water mill he carved himself, the innocent plaything of a hard worker, a fighter in a heavy battle. And in the small garden, the size of a palm, there are two small bridges, Kossuth’s and Rákóczi’s. Behind it again a small mill is bustling, but this one is already politicking like its owner when he is not at home but lives in Pest. This mill is a hammer mill, the one before was a Sagittarius, so it walks more slowly and wisely keeps on going: There it is – the country! There it is – the country! In one place, the ore widens into a lake: this is the Sea of Marmora, its shore is Tekirdağ, and on the island “an orphan stork stands alone” – thanks to Ottó Herman, who carved it like this.

(Kálmán Lambrecht)

(Elemér Vezényi’s sketch of Ottó Herman)

“You are called to be the apostle of the religion of the divinity of reason in Hungary; and called to shine the torch of your profound intellect into the as yet unknown or ill-understood mysteries of the eternal laws of nature. This is your vocation.”

(Letter from Lajos Kossuth to Ottó Herman, 17 November 1888)

His academic work and political engagement have developed in tandem. For him, the idea of Hungarian independence also meant the independence of Hungarian science. Ottó Herman’s political role model was Lajos Kossuth. His political career was fundamentally determined by his relationship with Kossuth and his unconditional respect for both his person and his politics. The two men were close friends, and in addition to frequent correspondence, Ottó Herman visited Kossuth twice during his emigration to Turin. Understandably, like Kossuth, the polymath rejected the Compromise of 1867, never accepting any state function, and even rejecting the idea of membership of the Academy. Ottó Herman was an elected member of the Hungarian Parliament for almost fifteen years. His political writings and public articles appeared regularly from the early 1870s in the press of the time. His work as a journalist made him a respected public figure. As a culmination of this process, thanks to the powerful support of Lajos Kossuth, he was elected as a representative in Szeged-Alsóváros. He began his first term in parliament in 1879 as a delegate of the FÜGGETLENSÉGI PÁRT. He represented the constituency of Szeged for two more terms, and then won a parliamentary seat for the fourth time as a representative of Törökszentmiklós. His last term in parliament (1893-1896) was as a representative of the town of Miskolc.

Girls of Miskolc

HOM HTD 76.713.9.1.

“The march took place with great enthusiasm (…). In the front was a band of gypsies, followed by three of us young girls with the National flag with the silk angel emblem in the national colour – with the inscription – long live Ottó Herman. After them the women – all in Hungarian. Followed by Ottó Herman in a four-horse carriage with two Independence MPs. Then a band of horsemen: a group of village men in southern village orphan hats, dancing their horses; even the horses’ manes were covered with national-coloured ribbons, and the endless cheering crowd.”

(The picture shows Mária Gyöngyössy’s recollection of the festive procession after the election victory in Miskolc)

(From a letter by Ottó Herman to Lajos Kossuth)

HOM HTD 53.4359.1.

“I have never ceased to work and agitate for the freedom of my nation. I study and know the country and its people. My creed: after my heart, my mind and my convictions, the Republic.”

In contrast to Ottó Herman’s richly researched scientific work, his private life is less well known. The great love of his youth was Mari Jászai, born in 1850. He met the then budding actress during his years in Cluj-Napoca. Their preserved correspondence reveals a lot about the relationship between the young actress and the scientist, who was also at the beginning of his career. The letters show that Mari Jászai was sincerely attached to Ottó Herman. The familiarity was often replaced by an intimate familiarity. Nevertheless, their relationship was never consummated. In 1869, Mari Jászai married Vidor Kassai, an artist at the Népszínház in Budapest.

Letters from Mari Jászai to Ottó Herman

HOM HTD 70.45.1-21

“My sweet dove, you are the best man on earth, and I love you the most I love on this earth”

(Extract from Mari Jászai letter to Ottó Herman)

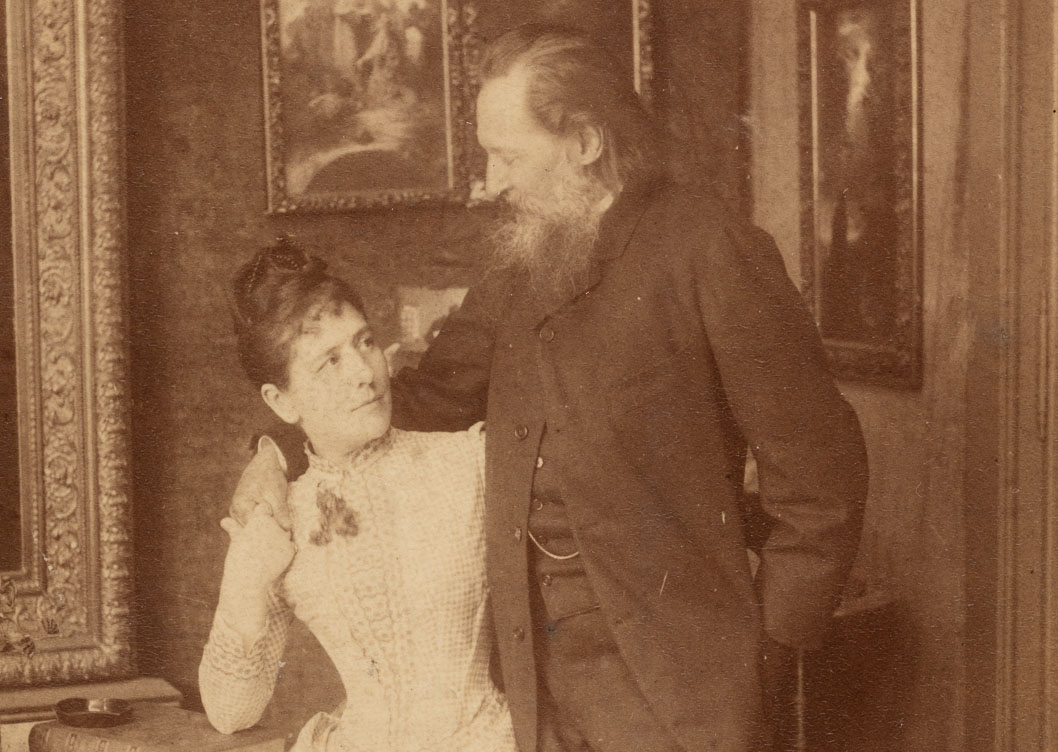

After the break-up with Mari Jászai, he devoted himself primarily to politics and science. When many people thought he would never marry, he asked Kamilla Borosnyay to marry him in 1885, and celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of his bachelorhood with a wedding. Ottó Herman had found a worthy companion, a loving partner. Kamilla Borosnyay, the daughter of the former forty-eighth major of the Hungarian Army, was born on 14 September 1846 in Kézdivásárhely.

Table photo of Ottó Herman and his wife

HOM HTD 53.247.40.

She started writing after her first marriage, publishing under the pseudonym Judith. She also came into contact with Ottó Herman through her articles, and they got into a minor dispute in the columns of the newspaper Ellenzék in Cluj.

“Judith’s article also caught Ottó Herman’s attention. He replied to it because he didn’t like it, when fallacies are spread by a public so little susceptible to truths, but eager to believe all fabrications. Judith replied to this too. With wit, skill, undeniable literary routine. The bachelor naturalist was in no mood to argue with a woman writer. What was he to argue with a woman’s speech when he had so many fine fishing terms to accumulate? The sensation of the bird-killings was slowly being forgotten. One fine day, however, he bumped into his good old friend Oszkár Borosnyay on the boulevard. […]

– Do you know who Judith is who forced me into a debate in the Opposition?

– Of course, I do, she’s, my sister.

– Like this? Tell him I admit it: he has a sharp pen.”

(Kálmán Lambrecht)

They met personally through his brother Oscar. When the scientist was ill with pleurisy, he lay alone in his room. Then “a slender, frail woman knocked on the door of Ottó Herman’s bachelor apartment. It was Judith, the sharp-feathered adversary. Her brother had told her who the patient was. She knew from the papers that she was writhing alone on her bachelor pad. So, she showed me into the sickroom. – I may have a sharp pen. But my heart could not bear to see one of the country’s first scientists wasting away by himself without a nursing hand by his side.” (Kálmán Lambrecht)

The wedding took place in July 1885. In Miskolc, in the church of Avasi, they swore eternal fidelity. At the age of fifty, Ottó Herman found a loving wife in Kamilla Borosnyay, who remained his faithful companion for the rest of his life.

Ottó Herman’s top hat

HOM TGY 70.1.5.2.

“On July 26, 1885, at 8 o’clock in the morning, my brother-in-law, Ottó Herman, Member of Parliament, and Kamilla Borosnyay, were sworn to each other in the church of Avas, – with the greatest possible simplicity, the vows were performed by Ignác Nagy, pastor, – I, my dear wife, as sister of the groom, my daughters and my son-in-law were present. – By chance, and to the great joy of all of us, but especially of the wedding parties, the bride’s brother Oszkár Borosnyay, the secretary of the Minister of Finance, arrived with his wife Rácz Hermine, from Rank, where Borosnyay was on leave. In the spacious old-fashioned church, with the weather being a little overcast, the wedding was truly touching. But the news of this wedding was a surprise, not only for our town but for the whole country, many people considered the newspaper reports about it to be a fake news, and letters arrived from all over the country asking about the reality of the affair. Although we were well aware of Ottó Herman’s very correct views on family life, his move was unexpected, but all the more welcome for us. All the more so because he was entering into the most sacred of unions with a woman worthy of him in every respect. – Their noble character and great liberality are the best assurances that they will mutually seek each other’s happiness for the rest of their lives. May God grant that they may attain the greatest possible happiness on this earth and enjoy it to the highest limits of human age!!!”

(Ottó Herman’s brother-in-law, Samuel Szűcs)

In the twilight of their lives, they had a close family friendship with the youth writer and children’s newspaper editor Lajos Pósa. Their correspondence reveals that Ottó Herman turned to Lajos Pósa’s wife, Lída Andrássy, and their daughter Sárika with sincere friendship, loving care and paternal affection. For the ageing scientist and his ailing wife, the Pósa family was a source of support in his last years. After Ottó Herman’s death, his widow was cared for by Mrs Lajos Pósa, and later part of their estate was also transferred to the Pósa family.

“Secret.

I am asked by many people: how can the deaf hear, how can the little one understands the voice of the bird, the chirping of the crumbling cricket? He hears, understands through a heart that lives and beats for him. But to many it is a secret for ever; – happy indeed is he to whom it is no secret.”

(Ottó Herman)

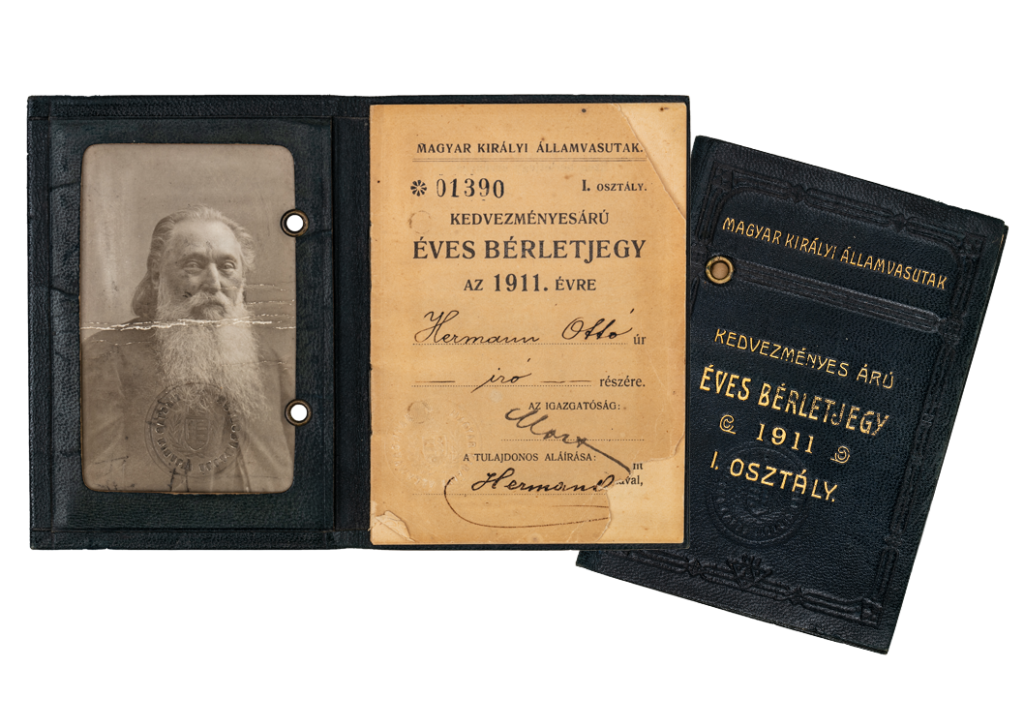

Ottó Herman’s railway pass

HOM HTD 70.53.2.

Kamilla Borosnyay’s railway pass

HOM HTD 70.53.1.

“Kamilla Borosnyay: For my husband’s name day (…) If God hears my prayer of heat, will give you a long and happy life. What I can give you you’ve had for a long time: My unbreakable, faithful, true love!!!”

HOM HTD 78.17.1.

Kamilla Borosnyay’s notebook

HOM HTD 70.51.1.

“What I like about this woman is that she takes the pen and writes the poem well, and then takes the spoon and cooks dinner well. That’s the criticism my father gave me, my father, who may have been wrong in the poem, but never in the dinner.”

(Excerpt from the diary of Kamilla Borosnyay)

HOM HTD 70.51.1.

“For my sweet, dear, to lark bird, nice, good Peleség Uncle Pele

24/XII, 1884.

I went from being a Peleség to a wife 26 July 1885. Lark”

HOM HTD 70.51.1.

Decorative box, text at the bottom Handwritten by Ottó Herman:

“my Pipiczi bird […] 1888. Uncle Pele”

HOM TGY 70.1.4.

His life was plagued by a variety of illnesses, and his childhood-onset asthenia proved fatal. The seventy-five-year-old scientist, lost in thought, was hit by a tram on József körút in Budapest. He recovered from his accident and threw himself into his work with renewed vigour. In December 1914, he suffered another fatal accident: in foggy, foggy weather, he could neither see nor hear the approaching carriage on Museum Boulevard. Lying in his flat with a broken leg, the very ill Ottó Herman contracted pneumonia and died on 27 December 1914. His funeral took place two days later in Kerepesi cemetery in Budapest.

In his will, he stipulated that he wished to be buried in Hamor, his tomb to depict a dying eagle carved from limestone. Half a century after Ottó Herman’s death, the town of Miskolc fulfilled his last wishes: in 1965, his ashes were laid next to his father’s returning ashes in the cemetery in Hámor, and later the tomb was unveiled. The cult of Ottó Herman – thanks to his wide-ranging oeuvre – developed in several scientific societies between the two world wars. His first monument was unveiled in the garden of the National Museum in Budapest in May 1930. His statue in Miskolc was erected in 1957 in front of the museum building named after him. Today, nearly thirty institutions, as well as many public spaces, social organisations and school competitions bear his name.

Ottó Herman raking in his garden

HOM FN 42.19.9.

The Pele House exhibition in Lillafüred was renewed in 2022. Scenario in Hospitality At Ottó Herman’s and, in keeping with this, he tried to turn the museum exhibition space into a holiday home from which the hosts had just gone somewhere, but anyone could visit them… The writer of these lines was not involved in the conceptualisation of the work, but only became part of it in the final, implementation stage.

The intimate closeness induced a number of questions, combining and meditating on them in an attempt to approach details that were perhaps little known or emphasized before…

Sámuel Szűcs [1819-1889] was the husband of Henriette Herrmann, and therefore Ottó Herman’s brother-in-law, a regular diarist lawyer from Miskolc. As a young man, Hámor – the Herrmann before the family settled there – he was a fan and admirer of its rocks, the Séléka the stalactite cave, hiking in its wild valley, boating on the lake. (István Dobrossy István-Kilián István ed. The diaries of Sámuel Szűcs (1835-1864) Miskolc, 2003. 152, 192, 224, 225.)

Sámuel Szűcs was one of the guides of Sándor Petőfi during his visit here, who in 1847. He wrote about Hámor on 8 July 1847, that “inside the village, where the hámor is, the valley becomes narrower and narrower, and at last it is completely surrounded by rocks, steep, wild rocks, and the road winds upwards along the banks of the Sinau, which forms numerous rapids, and at the top of the hill it gathers into a lake, whose water is dark green, as if it were a mirror of the forest of the surrounding hills. One thinks that he is at least in Helvécia, in one of the more beautiful regions of Helvécia” (Sándor Petőfi: Letters to Frigyes Kerényi).

The bathing resort and mountain style of 19th century bourgeois villa architecture is the Schweizerstil, Schweizerhausstil, or Swiss style. It is characterized by a gabled roof with wide eaves, a display of structure, ornately carved porches and gable walls. This style, which imitates the vernacular architecture of the Alpine countries, is spreading with the development of holiday homes in green areas near German, Scandinavian and Russian towns. In Hungary, it appeared in the 1880s through the transmission of pattern books and collections of patterns books and became characteristic not only of mountain resorts but also of resorts along Lake Balaton. In Siófok, for example, Ferenc Say designed most of the Swiss villas on Petőfi promenade and Batthyány street, while in Keszthely the Hullám Hotel, the Bath Island and the Rochlitz villa are striking examples of turn-of-the-century Swiss style. (Zoltán Bereczki. In Richárd Darázs (ed.): Avasi cobblestones. Zoltán Bereczki. Attila Balogh-Richárd Darázs (eds.): Postcards from the Palace. Miskolc, 2020. 42-43., Emőke Gréczi. Róbert Müller: Keszthely before yesterday, yesterday and today. Keszthely, 2005. 138, 154, 162.).

Ottó Herman, as the first predecessor of the future Pele House, had already bought the Lower Hamor farm from Lajos Kovács in a purchase contract dated 30 September 1889 in Miskolc. 122. property registered in the land register. One of the witnesses was Herman’s beloved brother-in-law, Samuel Szűcs, who passed away shortly after the sale. Just as importantly, he essentially bought additional and probably adjacent parcels of land from the State Treasury on 24 December 1898, but also from the aforementioned Lajos Kovács and even from the Grizak family, thus creating a property unit of a porch of sufficient size to build the Swiss-style Pele house.

Ottó’s stamp imprints

HOM TGY 70.1.1; 70.1.2.

Postcard of the Hamor waterfall

HOM HTD 70.42.20

A significant source of information about the days of Ottó Herman and his wife Kamilla Borosnyay in Lillafüred is the correspondence that has been preserved in the museum. They spend weeks together, but there are also periods when they spend their holidays at the Pele House without each other. A valuable piece is the postcard of the waterfall of Hamor, addressed by Ottó Herman from Lillafüred to his wife in Budapest on 14 August 1912 (HOM HTD 70.42.20.). 2 August 1907; 3 July 1907 HOM HTD 70.42.7, 70.42.9); postcard from Kamilla Borosnyay addressed to Sárika Pósa from Lillafüred and printed with a photo of the Pele House (24 August 1904 HOM HTD 70.43.3). It is interesting to note that he also writes a letter from Budapest to the Pósá family on paper with a photo of the Pele House on the header (16 July 1908 HOM HTD 70.43.2), and there is a letter from the Budapest publishing house Singer and Wolfner addressed to Kamilla Borosnyay in Lillafüred (24 July 1905 HOM HTD 70.44.14). According to Kálmán Lambrecht, the existence and national reputation of Lillafüred is due to Ottó Herman. Like him, ‘Count András Bethlen, Hungary’s Minister of Agriculture at the time, also visited the area a lot, and he also rested from the excitement of parliamentary battles in an undemanding hunting lodge in Lillafüred. The minister and the opposition MP met once on the shores of their shared ideal, Lake Hamor. It was at this meeting that the idea of Lillafüred as a bathing and resting place for the Hungarian middle class was born’ (Kálmán Lambrecht. In Lillafüred Spa Newspaper, 10 June 1933.)

Ottó Herman later becomes a local villa owner, increasing the area’s visitor numbers: “He spent the best summers of his productive life in Lillafüred. There, in that tiny corner where only forest hermits had hidden before. But since Ottó Herman settled there, it has become a famous holiday resort. The Budapesti Hírlap published more and more magazines and editorials about Lillafüred, and the number of visitors to Lillafüred increased. Any stranger who visited Miskolc would not fail to visit Lake Hamor and from there to the intimate mansion, in whose garden two tiny toy mills were crouched. The mansion was called Pele-háza and the mills were carved by the owner of the house, Ottó Herman.” In Lillafüred Spa Newspaper, 10 June 1933.)

Unfortunately, there are hardly any substantial data left about the equipment. It is a strange coincidence that the Zartl family’s bent furniture factory in Hamor, where they made Thonet-shaped chairs, hangers and other items from steamed beech wood, burned down in the year of Ottó Herman’s death. The curved furniture factory of the Zartl family. In: Borsod-Abaúj-Zemplén Megye Levéltári Évkönyve issue 14., Miskolc, 2006. 207-212.) Herman knew, perhaps even bought, furniture from the furniture factory that operated under the present-day Felsőhámor cliffs, on the site of the inn. In any case, he wrote in his location: ‘Approaching Alsóhámor, we come to a mill, opposite which on the slope rises a wild, partly towering rocky landscape, while in contrast a pure beech forest covers the mountainside. When we reach the lower end of the village, the valley forms a small bay, in which the factory of bent furniture stands, nestling in the rocky crevice, and behind it a narrow gorge of rock, to which a pass lead. In.)

According to Kálmán Lambrecht, “Whenever an encyclopaedia sent a questionnaire to Ottó Herman, the old man always wrote in calligraphic letters that he was born in Alsóhámor, Borsod County, on 28 June 1835. When I first visited him in his cottage in Lillafüred, we walked down to Alsóhámor, where he pointed to a deserted plot of land – with only one old plum tree standing on it – the site of my father’s house. I was born here”. (Kálmán Lambrecht. In.

According to Kálmán Lambrecht, Ottó Herman’s Hungarian temperament deliberately neglected Breznóbánya as a Saxon, let alone a Tartar settlement: ‘He declared himself so Hungarian that he broke with family traditions, even choosing his place of birth himself, just so that he could blend into Hungarianism without any residue’. A paragraph above, Lambrecht himself writes that “the birth certificate does prove that Károly Ottó Herrmann was born in Breznóbánya”, and then goes on to explain the details of the name change. In. We suspected, of course, that the last Hungarian polyhistor visited the central vineyard hill of Miskolc, the Avas, several times, but it is still a good feeling to record this with Sámuel Szűcs’ diary entry: ‘[1885.] September 18. Sámuel Szűcs married Ottó Herman’s sister Henriette on the second of June 1852 at their wedding in Hámor (István Dobrossy István-Kilián István. For example, in a letter to Emma Szűcs from Rózsahegy dated 2 September 1873, he wrote: ‘not a drop smaller than the Jewish church in Miskolc (…), the smallest is as big as the ref. (HOM HTD 53.4426.11) To Béla Szűcs from Vienna, 6 December 1873: “there are more weaklings than old shoes in Pecze” (HOM HTD 53.4426.1.33).

(Ottó Herman’s birthplace in Breznyóbánya)

Ottó Herman’s hearing was impaired from an early age. According to a popular anecdote, as a detrimental consequence of his mother, Károlyné Herrmann née Franciska Hammersberg Ganzstuch, hiding her boots in vain, her son ran off barefoot into the forests of the Bükk. The constant inflammation caused by repeated flatulence permanently damaged the child Ottó Herman’s hearing. Nowadays, new details are being whispered by the most avid beeches…

Just as in the freshwater estuary, the urban-natural frontier is also home to strange life forms with different characters. The Deep Valley between Kis and Nagyavas is cynically called Angel Valley when witches and dual-life beasts inhabit the cellar rows as neighbours to unsuspecting wine growers.

A bearded wolf, who moved from the Avas Mountains in Satu Mare to the Avas next to Szinva only a month ago, is now being searched for with a scythe and a hooded scythe. He rented a cellar at the top of the Deep Valley, pretending to be a wine merchant in human form. It is certain that the suspicious character is in fact a prig and that he devoured the tubber’s daughter and the diabolical day labourer.

What is the truth about this? Anyway, they can beat his footprints with sticks on the Iron. It runs through groves, through vast vineyards, across the Ruzsin towards the huts, it skirts the full-moon water, avoiding the busy people of the masses and huts. His witch is sought by the wolf, whose spiritual mate he became at the age of thirteen, when, as a trial from Satu Mare, came to the Beech for thirteen months. He still finds her after all this time, preserves her scent and flavours, and together they have grown from puppies in the past into an exceptional pair of adults. Basically, it is the witch’s telepathic message that has recently brought her back to the Borsod beech forest.

Well, what do you know, man-child! Barely fleshed, blonde, chiselled, he doesn’t mind, but he has to pay for the encounter somehow. He’ll live, but he’ll strengthen the aging wolf’s weary senses with the youth he’s gained from her. Almost obsessed, the child stares at a squirrel, as if the outside world did not exist. And there is…

The bearded one sneaks up close, what easy prey he’d be, no boots either on his feet! He deliberately steps on a dry twig, so that the crackling makes his head snap up and let the eyes merge, alarmed sky-blue with the all-knowing night black. How much time will pass in that haunting moment?

Strange words awaken in the depths of a child’s bewitched soul, they have no meaning yet, they are familiar but not from his mother tongue. He was born less than a decade ago among the Saxons, and here in the hámors of the Beech everyone speaks Luther’s language, and those who don’t, speak Tót. The wolf’s piercing eyes carve foreign words behind the child’s brow. “I’ll have your hearing, if you find me, you’ll have it back…” Then suddenly and with lightning speed the howler whirls, disappearing into the hollow of the hornbeam in the woods.

You don’t know how, the little child returns home, his mother and sisters at home they say, their mouths are not shut, their eyes are round, yet they are silent. The child mumbles something. ” Inyim hallasod, talalsz visszakap.” They continue to scold and scold, of course, but only the doctor who heals the smiths of the Hamor, the child’s father, becomes pale. He often hears the Hungarian speech of the farmers of Avasi who cart up the wine barrels and he has an idea of the nature of the bearded wolf. He knows well that his little son will be forced to wander the woods and fields, that he cannot be restrained, and that he should learn everything he can about animals and plants.

The doctor is an experienced and well-read man, but he cannot know all the details, and he has no idea that the bearded man is a Hungarian nobleman who pays handsomely for everything. In exchange for his hearing, the boy Ottó benefits from the wolf’s perseverance, keen insight, Hungarian virtue and courageous speech, and later even his beard will be similar. For the inspiring short story, see László Barcsai. In Dénes Papp (ed.): Tales from the hill. Avas Repositary of Values XIII-XIV. Miskolc, 2021. 48-51.)

For two years, between 1859 and 1861, Ottó Herman, a Hungarian soldier conscripted into the Austrian Imperial Army, served in the southern port town on the Dalmatian coast. Dubrovnik, a Croatian town that has since developed into a tourist destination, was then known by its Italian name, Raguza. Despite a tragic start – he was sent to Raguza as a border guard, serving 12 years as a punishment in the hated Habsburg imperial army – Ottó Herman became a lover of the Adriatic. So much so that in the spring of 1886 he honeymooned with his heart’s chosen one, Kamilla Borosnyay, in Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia).

Between the military years and the honeymoon, from January to July 1877, Ottó Herman continued to publish his experiences and memories of Ragusa, twenty years earlier, in the columns of the Vasárnapi Újság under the title Adriatic Pictures. This series of articles gave us an idea of the everyday life of the last Hungarian polymath in Dubrovnik and localised the scenes of his life there, above all his house. In the words of Ottó Herman: “A general officer (later my liberator and now a general) took advantage of me, and liked me, so instead of a kazama I was transferred to the Palazzo Conte Caboga, the most beautiful spot in Stradone, where the secrets of the general’s office were woven. The patrician knight came close to me and faithfully warned me of what to do; in front of me stood the domed cathedral built in the modern Italian style, and to my left the Dogana, which so vividly reminded me of the Doge’s palace in Venice, and which was in fact only a simplified, smaller image; I could just look down on the Porta Plocé, and I did so many times” (Sunday Newspaper, 3 June 1877).

Comparing all this with a map of Dubrovnik, we have come to the following conclusions:

– On the main street of Raguza, at the eastern end of Stradone (the southern Slavic name is Placa, or Stradun, which is more like the Italian original), Ottó Herman lived as a colonel in the headquarters of the General Staff office, near the clock-towered Porta Ploce/Ploce gate with its bell with a bell chimed with a coin bell.

– The Dogana, or Customs House, is identical to the Sponza family palace, which still stands today as Dubrovnik’s only truly Venetian-style building. Within its walls are archives, a clearly identifiable main street house, which Ottó Herman saw daily in the immediate vicinity of his apartment in Ragusa.

– Looking to the right of the customs office (Dogana/Palazzo Sponza), he mentioned the “modern Italian-style domed cathedral”. Ottó Herman probably built it here could not refer to the Dubrovnik cathedral, which is some distance away from the customs office, but to the church of St. Balázs, also domed and indeed adjacent to the one mentioned above.

After locating the surroundings, the author shared with us these words about his house: “The entrance to Stradone’s palaces is through the alleys, and there are as many alleys as there are houses. As the town is built on a hillside, Stradone forms the base of the valley, the alleys are mere staircases. The stairs are of rough marble, and as the ironing of footwear is unknown here, the whole town’s staircase is polished. Now, at the first resting-place of the alley stairs, I tilted the gate with the mallet hanging from it. (…) We were given the first floor: the Signora Contessa lived in the second, alone. She was an absolutely typical figure, and even if I were to summon up all my chivalry, and make up for it with the sincere respect I have for the fairer half of humanity, I can only say that the Contessa was a typical bitch: – but only in appearance, otherwise she was quite benevolent to the maledetto cane straniero (damned foreign dog – K. (…) The Contessa, being over sixty, was certainly a frightening creature. She lived in complete seclusion among her old almshouses in Sűette, and only the freezing Boro days would occasionally lure her down to our heated office. For here the stove was an unknown thing, and we had to bring our own. On bora-days, coals are heated in a small copper kettle, the kettle has two hoops on its hanger, into which thumbs fit: on this kettle, the palms and faces are then warmed, and all imaginable blankets are hung over the body. Our Contessa wore this kettle frequently, and gradually it became quite sulphurous with the dust of the coals, her more than poor clothes became dirty – the uncombed hair was here and there out of place under the black bonnet – all this, together with her owl-like face and piercing black eyes, certainly created the crone. It is the remnant of the once so great patriciate: and whole rows of houses are thus with a single occupant.” (Sunday Newspaper, 10 June 1877)

The last countess of a formerly important patrician family, the familia Caboga (Kaboga/Kaboge, or more Slavically Kabuzic), was Ottó Herman’s lodger in Ragusa. It is perhaps no coincidence that on the map of Dubrovnik, opposite the Sponza Palace and St. Balázs Church, to the west of them, there is a block of main street, the alley on the opposite side of which bears the name of this very family (Kaboge)… This block is numbered Stradun 1.), the Cele Café is located in it, and it can be concluded from the above that Ottó Herman lived in this building in Dubrovnik between 1859 and 1861. A commemorative plaque on its wall would be justified and useful from all points of view!

In the summer of 1888, he enjoyed the hospitality of his family fish processor in Kraaból, a farmer in the north of Norway, under the mountain of Svaerholt. The two-storey house with its many outbuildings, workshops and stables, and Lapland fishing hut, formed a tiny settlement in the Arctic wilderness. The house’s furnishings, with its huge family table, glass stools with commemorative glasses and cast-iron stove, reminded Ottó Herman of the burghers’ houses of the Spiš region, whose consumption habits were described in the travelogue: he appreciated the coffee and, of course, the ‘fish, milk, butter, cheese, the wafer-thin Norman bread – fladbröd – and the excellent tea’. (Compare Dunne, Linnea: Lagom. Budapest, 2017.)

The Hungarian ornithologist recalled his Norwegian hosts in an idealised way, saying that Kraa himself was “a splendid, sturdy and gracious Norman man”, and his wife was exceptional in the country, because she was, in Herman’s words, “the first full-bodied woman I ever saw in these parts”. On first meeting him, it turned out that he was ‘received like a member of the family by kindly people whose eyes radiated an unspoilt spirit’, and on parting, ‘the people of the house he has gathered in the valley. I took out my wallet; but old Kraab protested and hugged me; his son and brother grabbed my things (…). A warm handshake, another look at the northern fog bank, one at the honest faces of good men (…). As long as the colony of Svaerholt was visible, the waving of the shawls continued.” Ed. by Dénes Gábor. Bucharest, 1982. 209, 213, 219.)

He drinks coffee and is a heavy smoker until he is fifty. According to Kálmán Lambrecht, Ottó Herman smoked approximately a hundred cigarettes and ten cigars a day before his illness in 1885 but recovered from pleurisy under the care of his future wife, Kamilla Borosnyay, and never smoked again. (HOM HTD 53.4426.13) In terms of intimacy, it is a serene detail that the members of the Herman couple are recorded as signatories with the nicknames “Pele and Mutuj” in 1889. (HOM HTD 53.4426.1.33.) And a reflection on their Lillafüred connection from a letter written by Ottó Herman to Lidike Pósa in 1908: ‘Because it is the home that is ours! What a sweet comforting feeling it is. It pains me even to hear a good man say of our little plot in Lillafüred that the garden paths have been beaten up by weeds” (HOM HTD 70.42.12.)

Ottó Herman was born in Breznóbánya on 28 June 1835, the son of Károly Herrmann, a surgeon at the Treasury. His father was transferred in 1847, and so he and his family came to the village of Hámor in the Bükk Mountains.

His institutional education lasted at the Evangelical Gymnasium in Miskolc and the Vienna Polytechnic until the autumn of 1854, when the death of his father forced him to interrupt his studies to take a job as a breadwinner. The loss of the head of the family was unexpected and caught the family unprepared, as in July, Charles Herrmann (1802-1854) had organised spectacular fireworks display for the delighted bathers on Lake Hámori, and on the second of October he was buried on the hillside of Hámori. Sámuel Szűcs’ diaries (1835-1864) Miskolc, 2003. 285-286, 295.) The half-orphan Ottó Herman worked as a machinist for various Viennese companies, then he was drafted into the Imperial and Royal Army’s border regiment in Dalmatia. His pearl handwriting enabled him to serve in relatively good conditions as a regimental clerk in Ragusa/Dubrovnik. Having received his Obsit, he returned home to his mother in Hamor on 19 September 1861.

Soon his forester brother-in-law Nátán Scultéti was transferred to Ungvár, Ottó Herman’s mother went with the family of his daughter Ludmilla, and they left Hámor and the Bükk in January 1863 (István Dobrossy István-Kilián István ed. Sámuel Szűcs’ diaries (1835- 1864) Miskolc, 2003. 318, 327.). Ottó Herman then tried to join a photographer’s business in Kőszeg, and from 1 May 1864 he started to work as a curator of the zoological museum in the Transylvanian Museum Association under the direction of Sámuel Brassai, the chief museum keeper in the museum of Cluj-Napoca. Ottó Herman recalled the significance of his new job opportunity. Ed. by Dénes Gábor. Bucharest, 1982. 6.) Master and surrogate parent in one person was the scientist Brassai, since his young colleague had been orphaned in the meantime, Ottó Herman’s mother died in September 1869 in Ungvár.

In the spring of 1871, however, he left the museum and became a full-time journalist in Cluj, assistant editor of the Magyar Polgár. At that time, he had sensitive ties with Jászai Mari, who was playing in Cluj. Their meeting and secret love took place during the actress’s last season, when Ottó Herman also published writings on theatre. The spring of 1872 brought the tragic actress a contract at the National Theatre, from April she was already playing in the capital and from then on there was no trace of their further relationship. It is perhaps no coincidence that Ottó Herman also left the editorial staff of the Magyar Polgár in the summer of 1872 and left Cluj-Napoca.

At the request of the Natural History Society, he wrote and published the monograph The Spider Fauna of Hungary in three volumes between 1876 and 1879. This research made him nationally known. Before the publication of the first volume, in February 1875, he obtained a significant position in Budapest: he was appointed assistant keeper of the zoological gardens of the National Museum. He published regularly in various journals, including Vasárnapi

Postcard, Ragusa

HOM HTD 73.436.1.57.

Újság, Fővárosi Lapok, Nagyvilág, Borsszem Jankó and with special value in the pages of the Natural Science Gazette. His attention was increasingly focused on fish and ornithology. In four years, he wrote his second major monograph, in 1887 Ottó Herman’s two-volume work The Book of Hungarian Fishing was published. His brother-in-law, the diarist Sámuel Szűcs, also recalled his field research in Hámor: 23-24 September 1883 Ottó Herman “is now collecting data for his work on fish, for which purpose he was in Hámor today, where he brought back some fine specimens, one of which he also drew”. As a honeymooner, the young husband caught 450 trout in Hámor in August 1885! (István Dobrossy – István Kilián, ed. Sámuel Szűcs’ diaries (1865-1889) Miskolc, 2003. 177, 232.)

His commitment to independence led him to take a direct political role from 1879, when he was elected as a member of the Parliament of Szeged at the suggestion of Lajos Kossuth. He left his museum job, but Herman continued to edit the Natural History Bulletins for many years. He studied fishing in Szolnok and Tószeg, and the thematic material of the national exhibition of 1885 was not only arranged according to natural science aspects, but also the material culture and ethnography of fishing was given increased emphasis. In the summer of 1888, he spent two months in Norway, enriching his ornithological observations and experience.

The related cultures were an inseparable theme from the fauna of the mid-mountains of the Beech, the marine life of Dalmatia, the biology of spiders and fish. He studied pastoral life in the Karcag and Túrkeve areas, while he was a member of the parliament of Törökszentmiklós between 1889 and 1892. His mandate and the preparatory work for the section on ancestral occupations at the Millennium Exhibition, in connection with his interest in fishing, ornithology and pastoral life, linked his biography to the Hungarian Great Plain in the 1890s. By this time, he was already married (26 July 1885) to Kamilla Borosnyay, who was related to him from Szolnok, in the Reformed church of Avas in Miskolc. In terms of basic works, he remained indebted to the world of birds, which was a subject of constant admiration, but not until 1901, when his book On the Benefits and Harms of Birds was published and quickly became popular. By then he and his wife were spending their summers in their own Pele house in Lillafüred, a holiday resort in the upper part of the Hámor. The last great scientific triumph of his life was connected with the Bükk Mountains: he proved that contrary to the dominant opinion, prehistoric man did live in the area of the Seleta Cave and the Avas in Miskolc. He died in Budapest on 27 December 1914, the first year of the Great War. His grave in the Hamor cemetery is a scientific pilgrimage site.